Welcome to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your host and the flea on the hide of antiquity, Lucas Livingston. This is the second of a three-part series on dogs in antiquity.

Last time we explored the ancient hairless breeds of the New World and had a look at the popular ceramic funerary effigy of the Colima dog from a couple thousand years ago. We were also introduced to a young celebrity, Sputnik, my cute little hairless Xoloitzcuintli-Chihuahua mix.

Last time we explored the ancient hairless breeds of the New World and had a look at the popular ceramic funerary effigy of the Colima dog from a couple thousand years ago. We were also introduced to a young celebrity, Sputnik, my cute little hairless Xoloitzcuintli-Chihuahua mix.

Well, this time on the Ancient Art Podcast we’re heading away from the New World, back across the ocean, not to our familiar stomping grounds of the Mediterranean, but nevertheless to lands we’ve traveled before. We’re off to China!

Dogs and people have been tight for eons. Some of the earliest evidence for the domestication of dogs from wolves goes back about 12,000 years, well before concrete civilization took hold. [1] There’s archaeological evidence of dog-like remains in Belgium from about 30,000 years ago, but it’s thought that that might have been an isolated fluke with no descendants. [2] General consensus is that all modern breeds of dog evolved from the gray wolf. [2] One DNA analysis indicates that all breeds today stem from domestication of the gray wolf in China around 16,300 years ago, which was right around the same time as the domestication of wild rice. So it could be that wolves were domesticated at the same time when humans began to settle down into agrarian societies, and it’s tempting to see a connection there. [3]

Dogs and people have been tight for eons. Some of the earliest evidence for the domestication of dogs from wolves goes back about 12,000 years, well before concrete civilization took hold. [1] There’s archaeological evidence of dog-like remains in Belgium from about 30,000 years ago, but it’s thought that that might have been an isolated fluke with no descendants. [2] General consensus is that all modern breeds of dog evolved from the gray wolf. [2] One DNA analysis indicates that all breeds today stem from domestication of the gray wolf in China around 16,300 years ago, which was right around the same time as the domestication of wild rice. So it could be that wolves were domesticated at the same time when humans began to settle down into agrarian societies, and it’s tempting to see a connection there. [3]

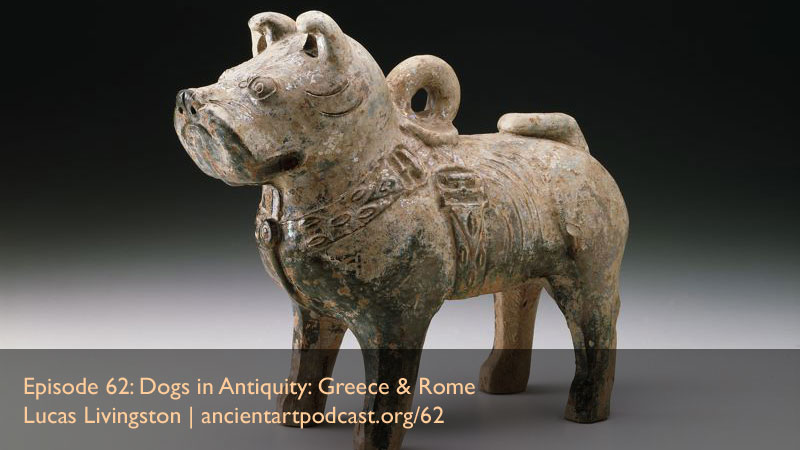

Fast forward some 14,000 years and we come to this clay statue of a dog in the Art Institute of Chicago from the Chinese Han Dynasty, roughly 200 BC to AD 200 (so, about 2,000 years ago and roughly contemporary to our Colima dog friend from last time). Typical of many funerary figurines of the Han Dynasty, the figure looks rather like something out of a cartoon, but we can certainly relate to it. The broad face, short muzzle, and powerful build might lead us to identify the breed as the mastiff.

Fast forward some 14,000 years and we come to this clay statue of a dog in the Art Institute of Chicago from the Chinese Han Dynasty, roughly 200 BC to AD 200 (so, about 2,000 years ago and roughly contemporary to our Colima dog friend from last time). Typical of many funerary figurines of the Han Dynasty, the figure looks rather like something out of a cartoon, but we can certainly relate to it. The broad face, short muzzle, and powerful build might lead us to identify the breed as the mastiff.

The Art Institute’s mastiff once stood watchful guard over the resident of a tomb. It may represent a trusty guardian and companion from real life, whom the owner wished to take with into the afterlife. The Han-dynasty Chinese called their tombs “subterranean palaces” (digong). [4] And as with any good palace, it would be decked out with all the great stuff you’d want in life and in death. This included wooden and ceramic models of guardians, servants, entertainers, miniature buildings, and indeed dogs. The industrial-strength restraints on the Art Institute’s mastiff betray the raw muscular power that the dog possessed. The colorful glaze that originally highlighted the bronze buckles, tan leather straps, and a shiny coat has deteriorated over time into a shimmering glimmer across the clay body.

The Art Institute’s mastiff once stood watchful guard over the resident of a tomb. It may represent a trusty guardian and companion from real life, whom the owner wished to take with into the afterlife. The Han-dynasty Chinese called their tombs “subterranean palaces” (digong). [4] And as with any good palace, it would be decked out with all the great stuff you’d want in life and in death. This included wooden and ceramic models of guardians, servants, entertainers, miniature buildings, and indeed dogs. The industrial-strength restraints on the Art Institute’s mastiff betray the raw muscular power that the dog possessed. The colorful glaze that originally highlighted the bronze buckles, tan leather straps, and a shiny coat has deteriorated over time into a shimmering glimmer across the clay body.

Over 1,000 years prior to our Han mastiff, archaeological remains of fire-cracked bones tell us something about how dogs were regarded in Chinese culture of the Shang dynasty. Turtle shell, bones of oxen, and other animals were cast into the fires by diviners of the Shang dynasty, something like the Marie Laveau’s of 3,500 years ago. The diviners interpreted the cracks in the bones caused by fire, much like reading tea leaves, palms, or cards, and inscribed those oracular prophesies on the bones. While it’s not uncommon for Shang oracle bones to be ground up by today’s apothecaries across China as medicinal dragon bones, thankfully some have escaped the mortar and pestle to be translated by scholars.

Translations of ancient fortunes inscribed on oracle bones inform us that concerned dog owners would visit the local divination shop in hope that occult magic might shed some light on the whereabouts of a beloved lost dog. And I confess that this seems infinitely more productive than posting “lost dog” signs throughout the neighborhood. But we also learn from oracle bone inscriptions that dogs were a favored stock for animal sacrifice. “Ah, yes, well,” said the diviner to an anxious customer, “The oracle bones remind me that your beloved missing Rover fulfilled an indispensable service for my earlier client.”

Thankfully, by the 5th century, straw dogs replaced real dogs as sacrificial victims for prophecy—yes, model dogs made of straw. The straw dog even makes an appearance in the 6th century BC Taoist philosophical text the Toa Te Ching (Dao De Jing) by Laozi (Lao Tzu). The passage is commonly translated as:

Thankfully, by the 5th century, straw dogs replaced real dogs as sacrificial victims for prophecy—yes, model dogs made of straw. The straw dog even makes an appearance in the 6th century BC Taoist philosophical text the Toa Te Ching (Dao De Jing) by Laozi (Lao Tzu). The passage is commonly translated as:

“The sky and the earth do not care,

They regard the myriad things as straw dogs;

The sage does not care,

He regards people as straw dogs.” [5]

While the straw dog was a great step forward in canine rights, dogs continued to be butchered in ancient China for burial and for food. Yes, food!

Much as we discovered last time in our discussion of dogs in the ancient Americas, there’s firm evidence of dogs as food in ancient China. In fact, if one looks hard enough at the archaeological or literary evidence, dogs as a source of protein can be found at some point in time in nearly every region across the world.

Be sure to check out our next episode as we wrap up our canid trilogy and head back home to the Mediterranean for a look at dogs in the Greco-Roman world.

If you dig the Ancient Art Podcast, be sure to “like” us on Facebook at facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and give us a nice 5-star rating on iTunes. You can follow me on Twitter @lucaslivingston and can subscribe to the podcast on YouTube, iTunes, and Vimeo, where you’ll hopefully give us a good rating and leave you comments. You can also email your questions and comments to me at info@ancientartpodcast.org or use the online form at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org. Thanks for tuning in and see you next time on the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2014 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[3] ibid. p. 28.

[5] Laozi, Tao Te Ching, Chapter 5. (Wikisource translation).

Another translation:

“Heaven and earth are ruthless, and treat the myriad creatures as straw dogs;

the sage is ruthless, and treats the people as straw dogs.”

From Chapter 5. Translation from Chen Guying ed. Laozi zhu yi ji ping jie 老子注譯及評介 (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1984) at 78.

Here’s a great blog post commenting on the interpretation of this passage:

“Chapter 5 – Straw Dogs.” The Blog at Ralston Creek Review. June 18, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

———————————————————