Greetings ghouls and gals. Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your ghost of a host, Lucas Livingston. In the spirit of Halloween, with monstrous fiends and tortured souls lurking about in dark shadows, I bring you this haunting episode of a mythic monster from the Classical world, the Gorgon Medusa.

Greetings ghouls and gals. Welcome back to the Ancient Art Podcast. I’m your ghost of a host, Lucas Livingston. In the spirit of Halloween, with monstrous fiends and tortured souls lurking about in dark shadows, I bring you this haunting episode of a mythic monster from the Classical world, the Gorgon Medusa.

In the lineage of the earth goddess, Gaia, Medusa is a chthonic being, a creature born of the chaotic shamblings from Earth’s dark abyss, much as we encountered in previous episodes exploring dragons from ancient myth and legend, like Python and Typhon. The monstrous Medusa is well known to modern souls, so fiendishly ugly with twisting snakes for hair that a brief gaze upon her visage will transform you to stone.

In the 7th century BC poem Theogony, among the litany of the origins of the myriad of hybrid monsters and creatures conjured up in the minds of the Greeks or imported from neighboring cultures and myths, the poet Hesiod mentions the children of Ceto and Phorcys, themselves sister and brother by the earth goddess Gaia and the primordial sea Pontus. Among these children are Medusa and her two sisters, collectively known as the Gorgons, from the Greek word γοργός meaning grim, fierce, or terrible.

In the 7th century BC poem Theogony, among the litany of the origins of the myriad of hybrid monsters and creatures conjured up in the minds of the Greeks or imported from neighboring cultures and myths, the poet Hesiod mentions the children of Ceto and Phorcys, themselves sister and brother by the earth goddess Gaia and the primordial sea Pontus. Among these children are Medusa and her two sisters, collectively known as the Gorgons, from the Greek word γοργός meaning grim, fierce, or terrible.

“And again, Ceto bore to Phorcys the fair-cheeked Graeae, sisters grey from their birth … and the Gorgons who dwell beyond glorious Ocean in the frontier land towards Night where are the clear-voiced Hesperides, Sthenno, and Euryale, and Medusa who suffered a woeful fate: she was mortal, but the two were undying and grew not old. With her lay the Dark-haired One [Poseidon] in a soft meadow amid spring flowers. And when Perseus cut off her head, there sprang forth great Chrysaor and the horse Pegasus…”

Theogony, ln. 270, trans. Hugh G. Evelyn-White, 1914.

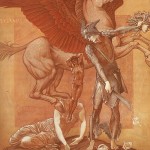

We learn a lot from that short passage in the Theogony. We learn that the Gorgons were sisters to the Graiae. Those are the three elderly crones who share one eye and one tooth between them. And we learn about the three Gorgons, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. While Stheno and Euryale are immortal, Medusa learns the hard way that she, indeed, was not. Perseus, the hero of the modern film The Clash of the Titans, beheaded Medusa. And he was extra clever about it. As Medusa’s gaze would petrify any onlooker, Perseus observed Medusa indirectly through the reflective surface of the mirrored shield he had received from the goddess Athena. In the Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid recounts the tale as Perseus approaches the lair of the Gorgon:

We learn a lot from that short passage in the Theogony. We learn that the Gorgons were sisters to the Graiae. Those are the three elderly crones who share one eye and one tooth between them. And we learn about the three Gorgons, Stheno, Euryale, and Medusa. While Stheno and Euryale are immortal, Medusa learns the hard way that she, indeed, was not. Perseus, the hero of the modern film The Clash of the Titans, beheaded Medusa. And he was extra clever about it. As Medusa’s gaze would petrify any onlooker, Perseus observed Medusa indirectly through the reflective surface of the mirrored shield he had received from the goddess Athena. In the Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid recounts the tale as Perseus approaches the lair of the Gorgon:

“Along the way, in fields and by the roads, I saw on all sides men and animals—like statues—turned to flinty stone at sight of dread Medusa’s visage. Nevertheless reflected on the brazen shield I bore upon my left, I saw her horrid face.

“When she was helpless in the power of sleep and even her serpent-hair was slumber-bound, I struck, and took her head sheer from the neck. To winged Pegasus the blood gave birth, his brother also, twins of rapid wing.”

Metamorphoses iv, 780-790, trans. Brookes More, 1922.

And in a manner of speaking, Medusa has children. In both passages, Hesiod’s Theogony and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, we learn that the blood spilt from the severed head of Medusa gave birth to two creatures, brothers, Chrysaor and the winged horse Pegasus. Yes, the majestic Pegasus sprung from the gore of Medusa. We’re all too familiar with Pegasus, from fairly tales and My Little Pony to Clash of the Titans and Dungeons & Dragons. And to be entirely faithful to Greek legend, there was only one Pegasus.

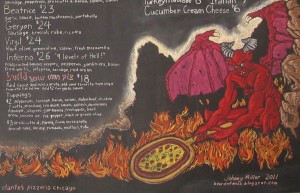

And in a manner of speaking, Medusa has children. In both passages, Hesiod’s Theogony and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, we learn that the blood spilt from the severed head of Medusa gave birth to two creatures, brothers, Chrysaor and the winged horse Pegasus. Yes, the majestic Pegasus sprung from the gore of Medusa. We’re all too familiar with Pegasus, from fairly tales and My Little Pony to Clash of the Titans and Dungeons & Dragons. And to be entirely faithful to Greek legend, there was only one Pegasus. Not like the teaming hoards of unicorns and fire mares. We don’t hear much about Chrysaor, though. His name essentially means “the dude with a golden weapon,” and, yeah, that’s pretty much all there is to say about Chrysaor, except that he also had a son named Geryon, which is the name of a pretty wicked slice at Dante’s Pizzeria in Chicago.

Not like the teaming hoards of unicorns and fire mares. We don’t hear much about Chrysaor, though. His name essentially means “the dude with a golden weapon,” and, yeah, that’s pretty much all there is to say about Chrysaor, except that he also had a son named Geryon, which is the name of a pretty wicked slice at Dante’s Pizzeria in Chicago.

Back to the matriarch, though. Medusa wasn’t always such a beastly monster. In fact, even ancient authors relished in the ambiguous appearance of Medusa, at once both beautiful and terrifying. In an ode written in 490 BC, Pindar speaks of “fair-cheeked Medusa.” A few examples of Greek vase painting depict the slumbering Medusa as not entirely unattractive. And many later images show a much more attractive Medusa. A few lines later in that passage from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Perseus recounts the background story behind Medusa—the cruel curse that damned this once beautiful maiden:

Back to the matriarch, though. Medusa wasn’t always such a beastly monster. In fact, even ancient authors relished in the ambiguous appearance of Medusa, at once both beautiful and terrifying. In an ode written in 490 BC, Pindar speaks of “fair-cheeked Medusa.” A few examples of Greek vase painting depict the slumbering Medusa as not entirely unattractive. And many later images show a much more attractive Medusa. A few lines later in that passage from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Perseus recounts the background story behind Medusa—the cruel curse that damned this once beautiful maiden:

“Beyond all others she was famed for beauty, and the envious hope of many suitors. Words would fail to tell the glory of her hair, most wonderful of all her charms—A friend declared to me he saw its lovely splendour. Fame declares the Sovereign of the Sea attained her love in chaste Minerva’s temple. While enraged she turned her head away and held her shield before her eyes. To punish that great crime Minerva changed the Gorgon’s splendid hair to serpents horrible. And now to strike her foes with fear, she wears upon her breast those awful vipers—creatures of her rage.” Metamorphoses iv, 792-802, trans. Brookes More, 1922.

So, to translate that poetic speech, Medusa was raped by the god Poseidon in the temple to Athena. As punishment for apparently allowing herself to fall victim to the attack on sacred ground of the virgin goddess, Athena transformed the beautiful Medusa into the fiend we commonly know.

At the end of that passage, Ovid also mentions the aegis, or the gorgonian, the face of Medusa worn upon the breastplate of Athena. Upon completion of his quests, Perseus gave the severed head of Medusa to Athena, which thereafter she would proudly sport as an apotropaic device, meaning to “turn away.” Even today the aegis is regarded as a talisman to ward off the evil eye, not unlike the Eye of Horus in some cultures today. Interestingly, the aegis and the Eye of Horus share much in common.

At the end of that passage, Ovid also mentions the aegis, or the gorgonian, the face of Medusa worn upon the breastplate of Athena. Upon completion of his quests, Perseus gave the severed head of Medusa to Athena, which thereafter she would proudly sport as an apotropaic device, meaning to “turn away.” Even today the aegis is regarded as a talisman to ward off the evil eye, not unlike the Eye of Horus in some cultures today. Interestingly, the aegis and the Eye of Horus share much in common.  In addition to both being protective talismans, they are both severed body parts, rent from the whole corpus in acts of violence. Despite that, they were both culturally and spiritually considered complete symbols in their own right—not mere fragments dislodged from some previous host. Both also entwine serpentine imagery about the central protective device.

In addition to both being protective talismans, they are both severed body parts, rent from the whole corpus in acts of violence. Despite that, they were both culturally and spiritually considered complete symbols in their own right—not mere fragments dislodged from some previous host. Both also entwine serpentine imagery about the central protective device.

Historians have often suggested that Medusa was not entirely the creation of the Ancient Greeks, but that she was part of a vast inheritance of myths, religion, and imagery from the Ancient Near East and from the Greek Bronze Age Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. [1] It’s been suggested that the primordial Medusa could have been a snake goddess, a mistress of beasts, or perhaps a solar deity. [2] The Egyptian Eye of Horus is closely connected to the Egyptian snake goddess, Wadjet, the patron goddess of Lower Egypt, the Nile’s delta region. We often see Wadjet depicted as the uraeus, the snake entwined about the solar disk surmounting the heads of gods and perched upon the crown of Pharaoh. Wadjet and the Eye of Horus are quite conceivably one of the many pre-Greek influences that shaped the Gorgon Medusa.

The origins and imagery of Medusa is a startlingly vast topic, so we can only scratch the surface here. But do stay tuned for a future episode delving deeper into the primal realm of that nether being, the Gorgon Medusa. We’ll dare confront the petrifying gaze of the monstrous fiend as we closely examine wondrous salient works of ancient art exploring Medusa’s roots, influences, and evolutions.

The origins and imagery of Medusa is a startlingly vast topic, so we can only scratch the surface here. But do stay tuned for a future episode delving deeper into the primal realm of that nether being, the Gorgon Medusa. We’ll dare confront the petrifying gaze of the monstrous fiend as we closely examine wondrous salient works of ancient art exploring Medusa’s roots, influences, and evolutions.

Thanks for tearing in to the Ancient Art Podcast. Be-head yourself on over ancientartpodcast.organs to gorge yourself on a feast of high-resolution imagery with detailed credits for this and other episodes, and to chant the eldrich scroll that is the transcript. Your witch’s mirror of clairvoyance can scry the actions of the Ancient Art Podcast at http://facebook.com/ancientartpodcast and http://twitter.com/lucaslivingston. Do inscribe your mythic runes of commentary upon the walls of YouTube, iTunes, and Vimeo. And evoke the uncanny oracle of the podcast through diabolical incantations at http://feedback.ancientartpodcast.org or alight your broomstick to the email address of info@ancientartpodcast.org. As always, the shambling hoards of the Abyss and I, your host, Lucas Livingston, thank you for tuning in to the Ancient Art Podcast.

©2012 Lucas Livingston, ancientartpodcast.org

———————————————————

Footnotes:

[1] Gisela M. A. Richter, “A Bronze Relief of Medusa,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Mar., 1919), pp. 59-60.

[2] A. L. Frothingham, “Medusa Apollo and the Great Mother,” American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 15, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1911), pp. 349-377.

———————————————————

See the Photo Gallery for detailed photo credits.

Credits:

Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959)

New York Public Library

University of North Carolina Greensboro Special Collections & University Archives

Classical Art Research Center & the Beazley Archive

Johnny Decker Miller, beardofmoss.blogspot.com

Apple

Creepy sounds courtesy of The Freesound Project, created by the following artists, and remixed by Lucas Livingston:

DJ Chronos, Horror Drone 001-006 (ID’s: 52134, 52135, 52136, 52137, 52138, 52139)

DJ Chronos, Suspense 001, 004-015, 017 (ID’s: 56885, 56886, 56887, 56888, 56889, 56890, 56891, 56892, 56893, 56894, 56895, 56896, 56897)

Sea Fury, Monster (ID: 48662)

Sea Fury, Monster 2 (ID: 48673)

digenisnikos, scream3 (ID: 44260)

thanvannispen, scream_group_women (ID: 30279)

rutgermuller, Haunting Music 1 (www.rutgermuller.nl) (ID: 51243)